йҮҚеЎ‘дәәзұ»еҺҶеҸІзҡ„йј з–«пјҢеҲ°еә•жқҘиҮӘе“ӘйҮҢпҪңеӨ§иұЎе…¬дјҡ( еӣӣ )

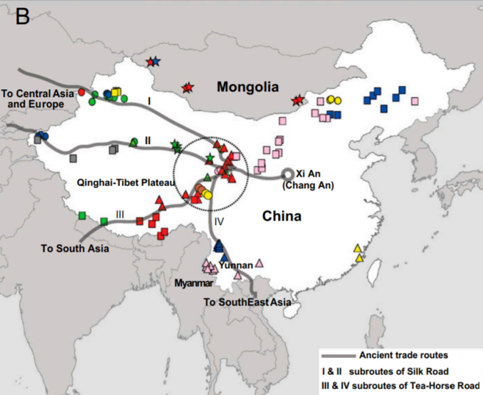

В· жҚ® Historical Variations in Mutation Rate in an Epidemic Pathogen, Yersinia pestisпјҲ2013пјү пјҢ йј з–«жқҶиҸҢеҸҜиғҪжәҗиҮӘйқ’и—Ҹй«ҳеҺҹжҲ–йҷ„иҝ‘ең°еҢәиҖҢж №жҚ® 2015 е№ҙе’Ң 2019 е№ҙзҡ„з ”з©¶ пјҢ ж—©еңЁзәҰ 5000 е№ҙеүҚ пјҢ 欧жҙІдҫҝе·Іжңүдәәзұ»ж„ҹжҹ“йј з–«жқҶиҸҢ пјҢ иҝҷдәӣйј з–«жқҶиҸҢзҡ„е…ұеҗҢзҘ–е…ҲеҸҜиҝҪжәҜеҲ° 5783 е№ҙеүҚ гҖӮ йј з–«жқҶиҸҢеҫҲж—©дҫҝжёёиҚЎдәҺ欧дәҡеӨ§йҷҶ пјҢ дёҚиҝҮж—©жңҹзүҲжң¬зҡ„з—…иҸҢ并没жңүеӨӘејәзҡ„иҮҙз—…жҖ§ пјҢ иҖҢдё”дёҚиғҪйҖҡиҝҮи·іиҡӨдј ж’ӯ гҖӮ еңЁеҗҺжқҘжј«й•ҝж—¶й—ҙзҡ„жј”еҢ–иҝҮзЁӢдёӯ пјҢ е®ғжүҚйҖҗжёҗе…·еӨҮдәҶжқҖдәәдәҺж— еҪўзҡ„з ҙеқҸжҖ§ гҖӮд»Һйј з–«зҡ„жү©ж•Јж–№еҗ‘д»ҘеҸҠйј з–«жқҶиҸҢе®ҝдё»зҡ„еҲҶеёғзңӢ пјҢ иҮӘй»‘жө·д»ҘдёңиҮідёӯеӣҪгҖҢеҚҠжңҲеҪўең°еёҰгҖҚзҡ„е№ҝиўӨиҚүеҺҹең°еёҰпјҲеҚіж¬§дәҡеӨ§иҚүеҺҹпјү пјҢ йғҪжҳҜйј з–«зҡ„жё©еәҠ гҖӮеҺҶеҸІдёҠ пјҢ е•ҶиҙёгҖҒжҲҳдәүгҖҒеҶңеһҰзӯүдәәзұ»иЎҢдёәйғҪдҝғиҝӣдәҶйј з–«зҡ„жү©ж•Ј гҖӮ еңЁдёӯеӣҪеўғеҶ… пјҢ дё»иҰҒзҡ„иҮӘ然疫жәҗең°дёәж–°з–ҶгҖҒз”ҳиӮғгҖҒеҶ…и’ҷгҖҒйқ’жө·гҖҒиҘҝи—ҸгҖҒдә‘еҚ—зӯүзңҒеҢә пјҢ еҲҶеёғдәҺй•ҝеҹҺжІҝзәҝд»ҘеҢ—д»ҘеҸҠи—ҸеҪқиө°е»Ҡ пјҢ 并жү©ж•ЈеҲ°дёңеҚ—жІҝжө· гҖӮ

В· дёӯеӣҪйј з–«иҮӘ然疫жәҗең° / жқҘжәҗпјҡгҖҠйј з–«пјҡжҲҳдәүдёҺе’Ңе№івҖ”вҖ”дёӯеӣҪзҡ„зҺҜеўғзҠ¶еҶөдёҺзӨҫдјҡеҸҳиҝҒпјҲ1230-1960пјүгҖӢиҝҪжәҜйј з–«жқҘиҮӘе“ӘйҮҢ并йқһжІЎжңүж„Ҹд№ү гҖӮ жәҜжәҗжҳҜдёәдәҶеҺҳжё…з—…еҺҹдҪ“еҸҠе…¶дј ж’ӯжңәеҲ¶ пјҢ д»ҺиҖҢйҒҝе…ҚжӮІеү§йҮҚжј” гҖӮ еҜ№дәҺйј з–«еҰӮжӯӨ пјҢ еҜ№дәҺе…¶д»–з–ҫз—…д№ҹжҳҜеҰӮжӯӨ гҖӮйј з–«жҳҜдёҖз§Қдәәз•ңе…ұжӮЈз–ҫз—… гҖӮ дәәзұ»ж–°еҸ‘дј жҹ“з—…дёӯ пјҢ жңү 78% дёҺйҮҺз”ҹеҠЁзү©жңүе…і гҖӮ 2019 е№ҙ 11 жңҲеҶ…и’ҷеҸӨеҮәзҺ°зҡ„йј з–«з—…дҫӢд»ҘеҸҠжңҖиҝ‘зҡ„ж–°еҶ з–«жғ… пјҢ йғҪиӯҰзӨәжҲ‘们иҝӣдёҖжӯҘеҰҘе–„еӨ„зҗҶдёҺйҮҺз”ҹеҠЁзү©д№Ӣй—ҙзҡ„е…ізі» гҖӮйј з–«жҲ–е…¶д»–з–ҫз—…зҡ„дә§з”ҹдёҺеҸ‘еұ• пјҢ 并дёҚеҸ—еӣҪз•Ңзҡ„йҷҗеҲ¶ гҖӮ е®ғ们зҡ„еЁҒиғҒеҜ№иұЎ пјҢ д№ҹдёҚеҸ—з§Қж—ҸгҖҒе®—ж•ҷгҖҒж„ҸиҜҶеҪўжҖҒзҡ„йҷҗеҲ¶ гҖӮ иҜёеҰӮдёӯдё–зәӘй’ҲеҜ№зҠ№еӨӘдәәгҖҒеҘіе·«зӯүзү№е®ҡдәәзҫӨзҡ„жұЎеҗҚеҢ– пјҢ жүҚжҳҜдёҖз§ҚзңҹжӯЈзҡ„дәәйҖ зҳҹз–« гҖӮ[1] жӣ№ж ‘еҹәпјҡгҖҠйј з–«жөҒиЎҢдёҺеҚҺеҢ—зӨҫдјҡзҡ„еҸҳиҝҒпјҲ1580-1644е№ҙпјүгҖӢ пјҢ гҖҠеҺҶеҸІз ”究гҖӢ1997е№ҙ第1жңҹ гҖӮ[2] жӣ№ж ‘еҹәгҖҒжқҺзҺүе°ҡпјҡгҖҠйј з–«пјҡжҲҳдәүдёҺе’Ңе№івҖ”вҖ”дёӯеӣҪзҡ„зҺҜеўғзҠ¶еҶөдёҺзӨҫдјҡеҸҳиҝҒпјҲ1230-1960пјүгҖӢ пјҢ жөҺеҚ—пјҡеұұдёңз”»жҠҘеҮәзүҲзӨҫ пјҢ 2006е№ҙ гҖӮ[3] еҙ”зҺүеҶӣгҖҒе®ӢдәҡеҶӣгҖҒжқЁз‘һйҰҘпјҡгҖҠйј з–«иҖ¶е°”жЈ®ж°ҸиҸҢзҡ„иҝӣеҢ–з ”з©¶пјҡд»Һзі»з»ҹеҸ‘иӮІеӯҰеҲ°зі»з»ҹеҸ‘иӮІеҹәеӣ з»„еӯҰгҖӢ пјҢ гҖҠдёӯеӣҪ科еӯҰпјҡз”ҹе‘Ҫ科еӯҰгҖӢ2013е№ҙ第1жңҹ гҖӮ[4] жқҺеҢ–жҲҗпјҡгҖҠзҳҹз–«жқҘиҮӘдёӯеӣҪпјҹвҖ”вҖ”14дё–зәӘй»‘жӯ»з—…еҸ‘жәҗең°й—®йўҳз ”з©¶иҝ°и®әгҖӢ пјҢ гҖҠдёӯеӣҪеҺҶеҸІең°зҗҶи®әдёӣгҖӢ2007е№ҙ第3иҫ‘ гҖӮ[5] йӯҸе…ҶйЈһгҖҒ尹家зҘҘпјҡгҖҠдёӯеӣҪйј з–«иҮӘ然疫жәҗең°з ”究иҝӣеұ•гҖӢ пјҢ гҖҠдёӯеӣҪдәәе…Ҫе…ұжӮЈз—…еӯҰжҠҘгҖӢ2015е№ҙ第12жңҹ гҖӮ[6] Aida Andrades Valtuena, Alissa Mittnik and Felix M. Key, "The Stone Age Plague and Its Persistence in Eurasia", Current Biology, vol. 27, no. 23 (2017), pp. 3683-3691.[7] Cui Yujun, Yu Chang, Yan Yanfeng, et al., "Historical Variations in Mutation Rate in an Epidemic Pathogen, Yersinia pestis", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 110, no. 2 (2013), pp. 577-582.[8] David M. Wagner, Jennifer Klunk, Michaela Harbeck, et al., "Yersinia pestis and the Plague of Justinian 541вҖ“543 AD: A Genomic Analysis", The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, vol. 14, no. 4 (2014), pp. 319-326.[9] George D. Sussman, "Was the Black Death in India and China?" Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol. 85, no. 3 (2011), pp. 319-355.[10] Giovanna Morelli, Song Yajun, Camila J. Mazzoni, et al., "Yersinia pestis Genome Sequencing Identifies Patterns of Global Phylogenetic Diversity", Nature Genetics, vol. 42, no. 12 (2010), pp. 1140-1143.[11] Jacob R. Marcus, The Jew in the Medieva1 World: A Source Book:315-1791, New York: Atheneum, 1979.[12] John Norris, "East or West? The Geographic Origin of the Black Death," Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol. 51, no. 1 (1977), pp. 1-24.[13] Joseph P. Byrne, The Black Death, London: Greenwood Press, 2004.[14] Michaela Harbeck, Lisa Seifert, Stephanie Hänsch, et al., "Yersinia pestis DNA from Skeletal Remains from the 6th Century AD Reveals Insights into Justinianic Plague", PLOS Pathogens, vol. 9, no. 5 (2013), e1003349.[15] Michael W. Dols, The Black Death In the Middle East, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1977.[16] NicolГЎs Rascovan, Karl-Göran Sjögren, Kristian Kristiansen, et al., "Emergence and Spread of Basal Lineages of Yersinia pestis during the Neolithic Decline",Cell, vol. 176, no. 1 (2019), pp. 295-305.[17] Rosemary Horrox (eds.), The Black Death, New York: Manchester University Press, 1994.[18] Simon Rasmussen, Morten E.Allentoft and Kasper Nielsen, "Early Divergent Strains of Yersinia pestis in Eurasia 5,000 Years Ago", Cell, vol. 163, no. 3 (2015), pp. 571-582.[19] Vincent J. Derbes, "De Mussis and the Great Plague of 1348", Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 196, no. 1 (1966), pp. 59-62.[20] William McNeill, Plagues and Peoples, Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/ Doubleday, 1976.

жҺЁиҚҗйҳ…иҜ»

- е…Ёдәәзұ»еҸӘжңүдә”дёӘдәәжҮӮиҮӘз”ұ

- зҫҺеӣҪз§Қж—Ҹжӯ§и§ҶдёәдҪ•еҰӮжӯӨдёҘйҮҚе‘ўпјҹ

- дёәдҪ•иҜҙзҫҺеӣҪ并没жңүйӮЈд№ҲејәеӨ§е‘ўпјҹ

- 欧жҙІдёәдҪ•ж— жі•з»ҹдёҖе‘ўпјҹ

- еҺҶеҸІзҡ„иғҢеҗҺ|еҠЈиҝ№ж–‘ж–‘зҡ„д»–еңЁзӢұдёӯ收еҲ°еҰ»еӯҗжқҘдҝЎпјҢеҮәзӢұеҗҺз–ҜзӢӮж®ӢжқҖ20дәәпјҢеҶ·иЎҖжҒ¶йӯ”

- дёӯеӣҪз–ҫжҺ§дёӯеҝғз§°з—…жҜ’并йқһд»ҺжӯҰжұүжө·йІңеёӮеңәеҗ‘дәәзұ»дј ж’ӯ

- еҺҶеҸІйҰ–ж¬Ў!иҢ…еҸ°и¶…и¶Ҡе·Ҙе•Ҷ银иЎҢ иҚЈзҷ»AиӮЎжҖ»еёӮеҖјз¬¬дёҖдҪҚ

- жҳҜе“ӘдёүдёӘеӣҪ家жҺЁиҝӣдәҶдәәзұ»зҺ°д»Јж–ҮжҳҺдё–з•Ң

- з©әй—ҙзҡ„жң¬иҙЁжҳҜд»Җд№Ҳпјҹ

- еҜ№дәҺдәәзұ»з”ҹеӯҳеҸ‘еұ•зӣ®зҡ„гҖҒж„Ҹд№үдёҺж №жң¬д»·еҖјзҡ„еҶҚи®ӨиҜҶ

![[иҗҢе® еӨ§жңәеҜҶ]иұӘеҚҺж„ҹдёҺеә“йҮҢеҚ—зңӢйҪҗпјҢж–°ж¬ҫе®ҫеҲ©ж·»и¶ҠSUVдә®зӣёпјҒ4.4TеҠЁеҠӣпјӢ马йһҚжЈ•еҶ…йҘ°](https://imgcdn.toutiaoyule.com/20200501/20200501104117573534a_t.jpeg)